Escalation of Commitment (Canadian Center for Architecture)

Written for the Canadian Center for Architecture

In 1900, ten Los Angeles-based businessmen signed Articles of Incorporation for the Automobile Club of Southern California (ACSC). There had been, at the end of that year, several Automobile Clubs across the nation established by and for the owners of a mere 4 192 automobiles, and in Los Angeles, that number was comparatively infinitesimal. During its first three years of operation, the club had only fifteen members, initially rendering it as a social club with little interest in advocating for the regulation of civic road construction. Yet with some of the most powerful land and business owners of Southern California on its staff and board of directors—including Harry Chandler, George Allen Hancock, and William G. Kerckhoff—the ACSC soon had cause to influence the centralization of Los Angeles as a national economic centre, whereby the automobile could be instrumentalized to reconstruct the city as an economic object.

A traffic jam in Downtown Los Angeles, 1920. Security Pacific National Bank Photo Collection

The club’s boosterism soon turned the organization into a victim of its own success. Los Angeles had become the city with the highest number of automobile fatalities in the United States by 1920. On any given weekday, more than 20 000 automobiles competed for space with bicycles, horse-drawn carriages, streetcars, and pedestrians along the narrow streets of Downtown Los Angeles, the centre of which had recently been designated the “Congested District.” Given that its streets had been laid out over thirty years prior to its accommodation of automobiles, it had become gridlocked by the disparate movements of varying modes of travel, each of which was guided by its own regulatory principles. Where streetcars ran on tight schedules along designated pathways and pedestrians braved the streets prior to the installation of official walking signals, the individualism of automobility had become an apparent threat to the city’s physical and economic health.

In April of that year, the City Council enforced a parking ban during business hours with the intent of reappropriating space for other modes of transportation while minimizing the presence of automobiles in the city centre altogether. Within a few days of its enactment, however, the ordinance had the adverse effect of robbing the city centre of nearly all commercial activity. The apparently stagnated flow of capital to the city’s economic centre became an ideal opportunity for the ACSC to escalate its commitment to the automobile’s presence in the city. In November 1920, the Club commissioned its chief engineer J.B. Lippincott to produce what the magazine Touring Topics deemed “probably the most complete study of traffic conditions ever made in the West.”1 As what was likely the first major traffic survey in the nation, it was a means of making informed recommendations for traffic alleviation. The club soon established an Engineering Department through which highway engineers regularly produced traffic studies and proposed solutions for expanding automobile infrastructure throughout Los Angeles, while its directors sat on multiple city-wide commissions to provide additional support to the automobile cause.

Cover of Traffic Survey: Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, 1937 © Automobile Club of Southern California. All Rights Reserved

In January 1937, the Club’s nine directors tasked the Roads and Highways Committee within its Engineering Department “to undertake a comprehensive traffic survey in the metropolitan area of Los Angeles for the purpose of formulating and submitting recommendations for the betterment of street and highway traffic conditions therein,” with Ernest E. East, a man once described as the “Father of Freeways” by the Los Angeles Times, acting as Chief Engineer.2 The following January, the department published Traffic Survey: Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, a landmark fifty-page report that its directors claimed would “increase safety in the operation of motor vehicles and will inevitably bring about a reduction of traffic accidents and loss of life and property damage in such accidents.”3 Throughout the report it is clear that, beyond the safety of motorists or pedestrians, the Engineering Department was principally concerned with safeguarding the automobile’s presence in the city as its primary mode of transportation.

Inwardly, the methods of data collection, measurement, and visualization presented throughout the report enabled the engineers to evaluate the movement of countless automobiles across the city—movement which had otherwise been made indecipherable by decades of rampant urban reform and related automobile use by a newly mobilized middle class. Outwardly, the report was intended to convince city officials and residents alike that despite the many threats posed by the widespread use of the automobile, its presence had overall positively contributed to the city’s economic growth, and should therefore be further accommodated by a network of motorways that would retroactively impose a sense of order onto Los Angeles following decades of chronic disorganization. This balance of self-criticism and praise is encapsulated in a single statement:

“Rail transportation forces centralization by confining business, industrial and residential development to areas served by such lines. Individual transportation, on the other hand, encourages decentralization, which in turn increases congestion and street and highway hazard. The widely scattered and intermingled shopping, industrial, cultural and residential districts of metropolitan Los Angeles, a condition for which the automobile is directly responsible, make the area peculiarly and vitally dependent upon the automobile for the major part of its transportation service.”4

Throughout, the report was devoted to visualizing the data collected by the department using three distinct methods that, each in their own way, represented the city’s urban form as a complex tapestry of time and space, whereby abstraction supposedly enabled a safer flow of people and goods. Yet in response to public concerns over the physical safety of Los Angeles residents moving across the city, the Automobile Club of Southern California foresaw the automobile as a mode of transportation under threat.

Aerial photograph of area of Los Angeles with varying densities, 1937 © Automobile Club of Southern California. All Rights Reserved

The first method delineated parking conditions across the city through a selection of aerial photographs taken by airplane—a technique they had employed as early as 1921. In addition to providing a holistic view of the city’s diverse forms of decentralization from an objective and authoritative position, the photographs were commissioned by the Engineering Department over several years to count the exact number of cars parked on streets with varying levels of population density during working hours to determine their impact on traffic conditions. “The spot aerial photographs show that the parking problem is not peculiar to the central business district,” the report claimed, “but exists in almost, if not equal intensity in every retail business center throughout the area.”5

Diagram showing origin of parked automobiles, 1937 © Automobile Club of Southern California. All Rights Reserved

The second method was to overlay diagrammatic information on top of the city’s true urban form at a variety of scales as a means of conveying the forces that created its then-current form of decentralization, as well as how that form had affected daily activity for its 1.3 million residents. One map, for instance, surveyed the origin of parked cars throughout the metropolitan area during working hours to uncover patterns of movement not apparent in the city’s urban form alone. The result is a dizzyingly tangled web of diagrammatic lines that virtually obliterate the existing street grid, rendering the innumerable statistics that went into its production illegible by design. Another diagram with similar intent isolated the “ribbon-like” development of business establishments in relation to other forms of land use along forty-five miles of a single street extending from Calabasas to the border of Orange County. By mapping the businesses that operated along narrow strips of land, as opposed to those within the city’s urban centre, the diagram highlighted the negative effects of land-use interference upon automobile transportation throughout the metropolitan area. The report claimed that the city’s low-density sprawl could be almost entirely attributed to the significant number of businesses that had been recently pushed out of Downtown by congestion.

Diagram showing geographical and driving time location of principal cities and towns in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area (centre is 7th and Broadway, Downtown Los Angeles), 1937. © Automobile Club of Southern California. All Rights Reserved

The third diagrammatic method re-envisioned Los Angeles as a centralized city by heavily abstracting its urban form and placing Downtown Los Angeles as its “true” physical centre to compare traffic patterns from the past and present. The smallest of four diagrams, complemented by tables that further mathematized the city into exact percentages of entry and egress, was a rectangular abstraction of the Central Business District showing the number of automobiles entering and leaving in 1929 vs. 1936. While the report as a whole indicated that Los Angeles had decentralized, these diagrams suggested that automobile traffic entering and leaving the city’s original centre had worsened nonetheless. In a separate diagram, the data from the thirteen pages of tables at the end of the report was synthesized into a circular map of the entire metropolitan area. Designating 7th and Broadway as a star at its centre, the diagram contrasted the physical locations of residential areas against the time it took for them to reach Downtown relative to six years prior, signaling an urgent crisis for the city: “the growing street and highway congestion is slowly but surely pushing the various communities farther and farther apart.”6

This assortment of data visualizations gave rise to a series of provocative images of a future Los Angeles whose primary function was to facilitate the flow of capital. Before the report’s introduction, for instance, a pair of aerial views of “motorways”—what we would now call freeways—produced by staff artist W. Neely were depicted barreling through two districts of contrasting density. The first was of an imagined residential district portraying the grade separations that East had championed for nearly two decades that would allow for a clear distinction between movement within the district and beyond it. Later in the report, it was stated that “in residential territory the center portion of the right-of-way should be paved to accommodate from four to six lanes of traffic, as required, with a physical barrier extending the full length of the motorway dividing opposing lanes of traffic,” while “the remaining land on each side should be planted to trees and shrubs.”7 “Through business districts,” the report proposed, “a right-of-way 100 feet in width should be acquired through or near the center of the block. On this land the so-called motorway building should be constructed. In general, the first and second floors of this building would be devoted to retail business, the third floor to the motorway proper, the fourth and fifth floors and as many additional floors as required to parking and the remaining floors to office space.”8 These visions of a city travelled across in three dimensions greatly contrasted with the then-present street network of Los Angeles, which was routinely burdened by competing modes of transportation buffered by commercial and residential buildings.

Map showing general location of proposed motorways by the Automobile Club of Southern California (1937) overlaid on top of the 1939 Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) “redlining” map depicting mortgage risks based on economic and racial criteria in central Los Angeles © Automobile Club of Southern California. All Rights Reserved

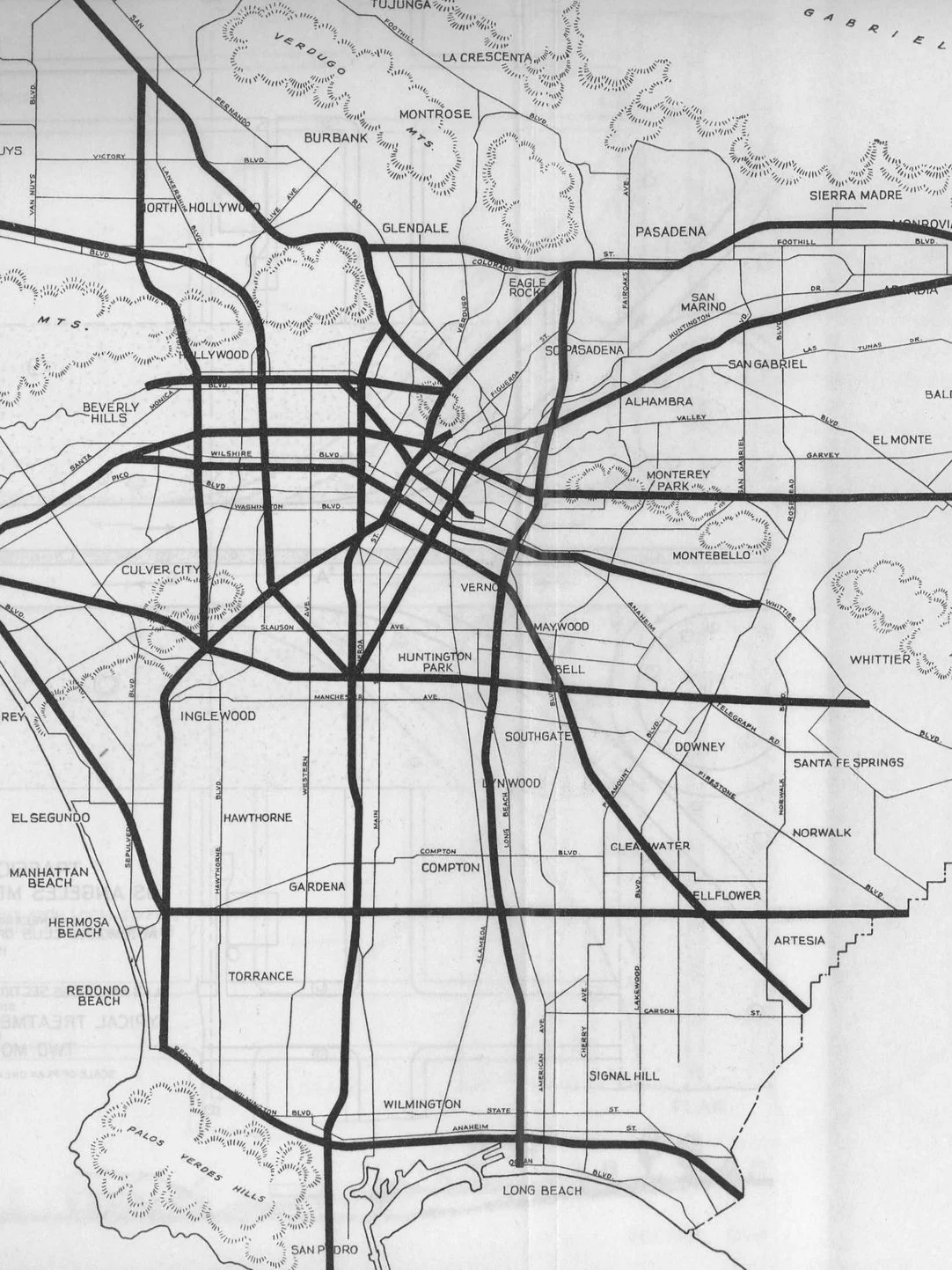

Perhaps the most visionary image in the entire report, however, was a fold-out map showing the “general location of proposed motorways in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area,” a network of elevated roadways entirely separate from the relatively antiquated streets below. Overlaying these proposed motorways on top of a map of Los Angeles depicting mortgage risks based on economic and racial criteria reveals that the Auto Club had envisioned the motorway cutting through several of the redlined neighborhoods (such as Boyle Heights and East Hollywood) while leaving the wealthier neighborhoods rendered in green (such as Beverly Hills and Westwood) relatively intact.

Covering far more ground than the freeway system that currently exists in the city, the proposed motorway network formed a dense lattice around and within the Congested Districts and radiated outward “through territory where the value of land and improvements is relatively low,”9 thus anticipating the racialized definition of “blight” that would warrant the destruction of predominantly Black and Mexican neighborhoods for the erection of a freeway system in the following decade. Assuring their readers that the proposal was not as ludicrous as the diagram may have made it appear, and was in fact an economically reasonable choice, they wrote that the motorways would “anchor both residential and business districts, greatly increase property values and raise the efficiency of the automobile to close to its rated capacity.”10 Alongside the interest paid to accelerating the movement of the city’s workforce, the attention paid to property values—both those of soon-to-be-blighted and well-to-do districts—as a determining factor for the layout of motorways reflects the ulterior interests of the board of directors, many of whom had been long-standing property owners in the wealthier portions of the region.

Though many of them were enormously wealthy in their own right, the board of directors had apparently requested the proposal from the Engineering Department as a means of persuading the city’s residents to foot the bill, arguing that they would only suffer financially in the long run if they failed to support it. “We have considered the ability of the taxpayers of the Los Angeles area to assume the large financial burden involved, and have answered the question in the affirmative after comparing the estimated cost distributed over a period of years with an estimate of what it is costing today to do without such facilities in loss of human life, injury to persons and property damage, blighted business and residential districts and mounting transportation costs.”11

In a short essay published in 1941—just a few years before the city would undergo an enormous procedure to erect an internal freeway system—East plainly expressed his final thoughts on the city he helped shape. “The solution of the transportation and land use problem of the Los Angeles Metropolitan district is, from an engineering and financing standpoint, a simple one,” he wrote. “It consists of developing over a period of years a network of motorways designed to serve transportation rather than land.”12 Alongside this remedy for “transportation fever,” East included a diagram borrowed from a traffic survey published in 1939 charting the coalescence of time, space, and money as speed, whereby an automobile trip across the city is shown to either take thirty-three minutes on surface streets relative to eighteen minutes on an “express highway.” Speed, then, became an economic criterion that would soon enough take shape as an expansive and elevated object, towering over the city to accelerate the flow of capital far more efficiently and safely than the oldfangled surface streets below.