Figural Monuments

Featured in Mas Context (The Legacy Issue)

Spring 2016

Pages 160 - 169

With Kyle Branchesi

“In LA, if there was a spot and you heard that Beyonce chipped a nail on that spot, then every time you passed it you’d be like ‘Ah, here’s that parking lot where Beyonce chipped a nail!’ And that means something, and you feel like a ghost, like a background character to this enormous stage, like nobody would ever notice you. Because in LA if you and 2000 people see a billboard and Beyonce is on it, you feel like this town belongs to her, and everyone else on the video store murals we’re just renting it from them, and wearing sunglasses and walking around pretending we belong.” -Zak Smith

Los Angeles is divided: some are celebrities, and the rest are not. The daily interactions that take place between these two classes create a distinct mental geography that is of great interest for non-celebrities; a map not invested in historic political events or natural disasters, but rather one at the intersection of the banal and the newsworthy. Figural Monuments (2014) is a project that attempts to commemorate the importance of celebrities to our collective memory. Memorials are placed at the sites of famous celebrity incidents and oversights around Los Angeles, and are disguised as governmental architecture one commonly sees within the city. The relationship between Los Angeles and Figural Monuments is linked to the city’s tenuous relationship with memory and its own history. This project challenges and confounds some of the issues that have often characterized the field of memorial design, as well as make permanent the celebrity mishaps that were once only gossip.

Figural Monuments honor celebrities over non-celebrities. Harris Demitropoulos, in attempting to establish the standards and ethics of memorial design, wrote that, “memorials [should] address their intended audience by accommodating a projection of the individual on their semantic matrix. As a subject, to be drawn to a memorial, I have to find a part of me in it.” While this may be a reasonable rule of thumb for many major cities, Los Angeles is uniquely divided by both automobile culture and fragmented communities. Their semantic matrix therefore lies not within themselves, but in celebrities to whom they have elected higher power and status. The constant stream of TMZ vans and Star Maps pamphlets for sale along Sunset Boulevard confirms the lengths to which the general population will hold celebrities over their heads.

Though it lacks the solidity and implied significance of some other major cities, Los Angeles has a mythology as strong as that of the Greeks in celebrity culture. Many locals will recall the corner of Fairfax and Wilshire when asked where Biggie Smalls was shot, and more still can point out the Saks Fifth Avenue that caught Winona Ryder shoplifting on videotape. Celebrity culture supplies the collective memory of Los Angeles for those outside and within for one reason: a lot of people shoplift and get shot, but when it happens to a celebrity, it becomes that much more interesting.

Figural Monuments confirm collective memory. On the subject of a city’s collective memory, Aldo Rossi wrote, “One can say that the city itself is the collective memory of its people, and like memory it is associated with objects and places. The city is the locus of the collective memory.” Buildings, like monuments, are used as landmarks as one navigates through a city.

And when a stately piece of architecture is coupled by a notable historical event (such as the Round Table meetings at the Algonquin Hotel in New York), it is easy to argue for a site’s significance. These sites become landmarks to those familiar with their history. Yet Los Angeles does not have many of these happenstances to speak of. We are yet to claim a Columbus Circle or a Garibaldi Square, either because the political events don’t happen here or we simply choose to look past them. Jan Rowen once observed that “to be able to choose what you want to be and how you want to live, without worrying about social censure, is obviously more important to Angelenos than the fact that they do not have a Piazza San Marco.”

Given these conditions, Figural Monuments gathered celebrity blunders and placed memorials exactly where they were rumored to take place. Some recall a murder or robbery, while others signify the videos of celebrities bumping their heads or tripping over sidewalks that once went viral. Their collective memory is not centered on political or academic achievements, but lies squarely on the minutia of any given celebrity's everyday life. As we pour over the details, we not only give them a higher status than non-celebrities, but we also validate the importance of their every move.

Many people are aware, for example, that Hugh Grant invited a prostitute to his car in 1995, but few know exactly where it took place. Automatic Teller Machine 00023d2 (Hugh Grant) [Figure 1] is located on the intersection of De Longpre and Courtney Avenue, the site of the allegation. Now that a memorial in visible at the site, visitors may visit to remember the famous incident at an otherwise insignificant intersection for pedestrians or automobile traffic.

Figural Monuments are Figural. Geometric abstraction was arguably popularized by Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial in Washington D.C in 1982. Prior to this point, memorials were almost entirely figural, embodying those honored with the highest level of verisimilitude and allegorical content. There were accompanying plaques with the honorees’ names and brief biographies, yet their focus was sculptures with faces and time-period clothes that were instantly recognizable and often scaled up. This was done to both increase their visibility and illustrate their importance. The Korean Memorial designed by Frank Gaylord, adjacent to the Vietnam Memorial, demonstrates the relative immediacy of the human figure in monumentality.

The current method of geometric abstraction assumes that its audience is not only actively literate, but will also take time to read further into the nature of a piece. However, to assume this type of audience in Los Angeles would be the first mistake in local memorial design. With a pedestrian culture that is still yet to be seen, Los Angeles requires signage that can be read quickly and from distant vantage points. As well, David Gebhard has observed, “California’s mildness of climate, with the resulting ability to cheaply and quickly erect structures, encourage[s] a non-serious view of not only architecture, but symbolism and salesmanship as well.” Sharp marble and concrete solids, when displayed earnestly, have little resonance here.

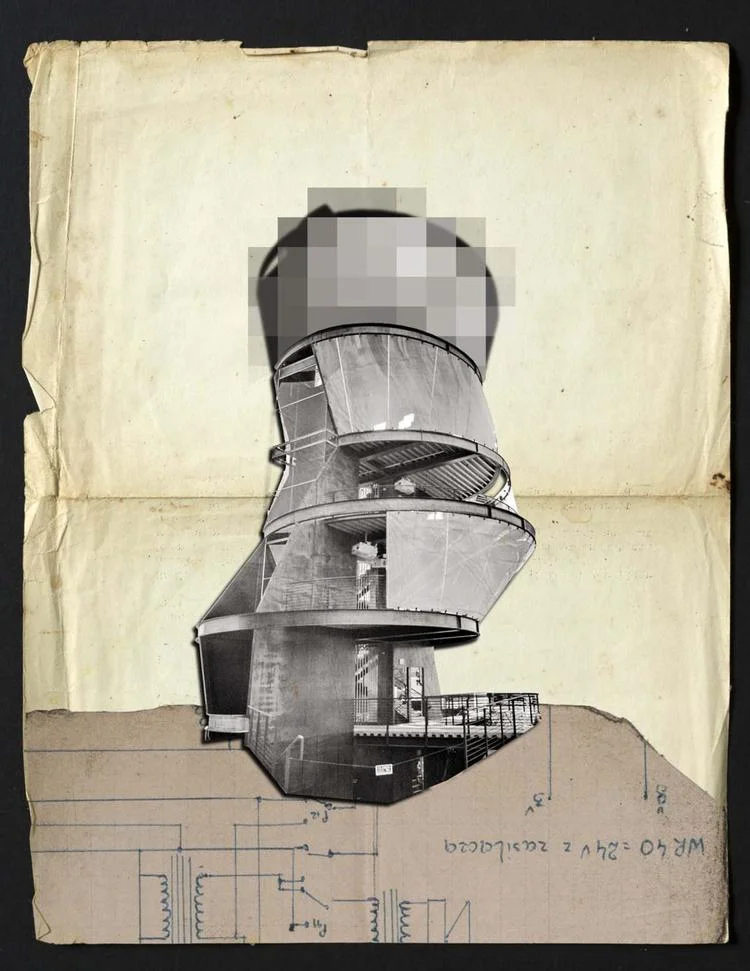

Bollards 2 and 3 (Kim Kardashian and Kanye West) [Figure 2] represent the memorable forms of the two celebrities at the exact moment the paparazzi distracted them from their walk out of a parking structure, resulting in Kanye West bumping his head. The bollards portray the body language that characterized the incident, and they are only present at certain times of the day.

Figural Monuments are obsessively site-specific and sometimes obstructive. Memorials have typically been placed in parks as traditional artwork have been in galleries: in the center or out of the way of a path of circulation that had been established before it. By their politeness, they are quickly accepted as memorials and do not leave room for speculation. Figural Monuments are more akin to the chalk outlines of murder scenes than its predecessors. This level of site specificity ensures that the gravity of one celebrity’s blunder is regarded as more essential to the way a city functions than the ease of movement for everyone else.

Biggie Smalls was murdered in front of The Petersen Automotive Museum on Fairfax and Wilshire. Though the permanence of this museum is currently under debate, the memory of Biggie Smalls dwarfs the architectural significance of this site and takes precedence. Bus Stop 775 - Wilshire/Fairfax Transit Hub (Biggie Smalls) [Figure 3] takes up the majority of the sidewalk, requiring pedestrians to purposefully walk around or under the memorial. It appears as a solid clash of concrete and marble above fragile furniture.

Detention Center 008 (Winona Ryder) [Figure 4] poses as a supplementary security room for the adjacent Saks Fifth Avenue. Its location across the street is, according to publicly viewed security footage, as far as Winona Ryder ran with the five stolen dresses, only to be apprehended moments later. The building strikes both shoppers and general pedestrians as patently absurd in its detachment and overall distance from the Saks to which it formally belongs.

Figural Monuments are disguised as city architecture. Because the impact of sculptures in parks or in front of buildings has diminished as they’ve been quickly regarded as ‘public art,’ new relationships between memorials and the cities they’re in have to be drawn. Contemporary artists have established flexibility in the category by considering new relationships between art and its environment. As Rosalind Krauss had observed in 1979: “Rather surprising things have come to be called sculpture [lately]: narrow corridors with TV monitors at the ends; large photographs documenting country hikes; mirrors placed at strange angles in ordinary rooms; temporary lines cut into the floor of the desert. Nothing, it would seem, could possibly give to such a motley of efforts the right to lay claim to whatever one might mean by the category of sculpture. Unless, that is, the category can be made to become almost infinitely malleable.” Architecture has often played a role in this categorical game, if not only because it has always been its backdrop and source of definition.

The Figural Monuments are therefore more covertly placed in their urban environment than their predecessors. They are programmatically based on familiar objects within the city, such as ATMs, security booths and bus stops. Rather than adorn standard box buildings with symbolic decoration like parade floats, the functionality of the series is willed by their outward figurality. The memorials therefore appear curiously out of place; like one-offs that stand proudly by their control groups.

Parking Meters 4800cc82 and 4800cc83 (Angelyne) [Figure 5] generally look and function like the other parking meters with which they share a row. But because they commemorate the time Angelyne attempted to avoid the paparazzi and her subsequent fall, these parking meters appear awkward and bashful compared to the rest. It seems that no plaque is necessary for viewers to interpret the mood of the incident that took place here, since none has been placed.

Figural Monuments are fictional. Marble, concrete, and granite have been the standard materials in memorial design for their apparent permanence and seriousness; this might be the one convention that continued from figurality to geometric abstraction without any major exceptions. These are heavy materials for heavy meaning, and a monument's physical presence is proof of an event's authenticity and importance. Many only see them in visual content and publications, yet fewer can claim to see the real thing. Monuments are an alternative for word-of-mouth and are intended to solidify memories in the ground.

But the rumors about celebrities are often only that, and these memorials attempt to reflect this instability. The Figural Monuments are real as far as images are three-dimensional; they are five postcards exhibiting the images that accompany this essay, and nothing as of yet has been erected at the sites they describe. These postcards confirm collective memories to many through nearly weightless distribution, performing in a similar fashion to the social media that has lately become prevalent.

--------------------------------------------------------

The intention of this series is not to remind viewers of what would otherwise be forgotten, but rather to confirm what was generally brushed off as mere gossip. With Figural Monuments, our celebrity Schadenfreude is validated and our collective memory fortified. Los Angeles is torn between the have and the have-nots, a condition either self-inflicted or projected onto it by the rest of the world, and it is time to acknowledge this reality through intensive memorialization. Similar hierarchies exist in other cities - gangsters in Chicago, founding fathers in Philadelphia - but arguably none confound the concepts of civic memory and rights to fame quite like Los Angeles.