City of Memes (Los Angeles Review of Architecture)

Growing up in the San Fernando Valley—a patchwork of suburbs north of the mountain range that splits Los Angeles in two—I thought the city’s borders touched tips on the opposite side of the planet. From the overlooks along Mulholland Drive, a smog-capped horizon marked the visual limit of an endless landscape, beneath which every conceivable architectural style and type had found a place and some breathing room. Everyone on earth was more or less a resident.

Later, I learned that the megalopolis truly did have an outside. Not only that—it demands to be read from the outside. Cultural and urban studies are strewn with the vain and failed attempts of visiting critics to make sense of the area’s contours. Los Angeles has been described by Christopher Hawthorne, the former architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times, as the quintessential “hard-to-read” city—a borderless place that dares out-of-towners to sling mud at its self-portrait to see what sticks. Hawthorne follows the architect Charles Moore (an honorary Angeleno himself ) in arguing that interpreting LA whole cloth requires “an altogether different plan of attack.” The challenge is put into sharper focus when we acknowledge that the city has been so shaped by mass media that it cannot be approached using the old, familiar methods of urban criticism.

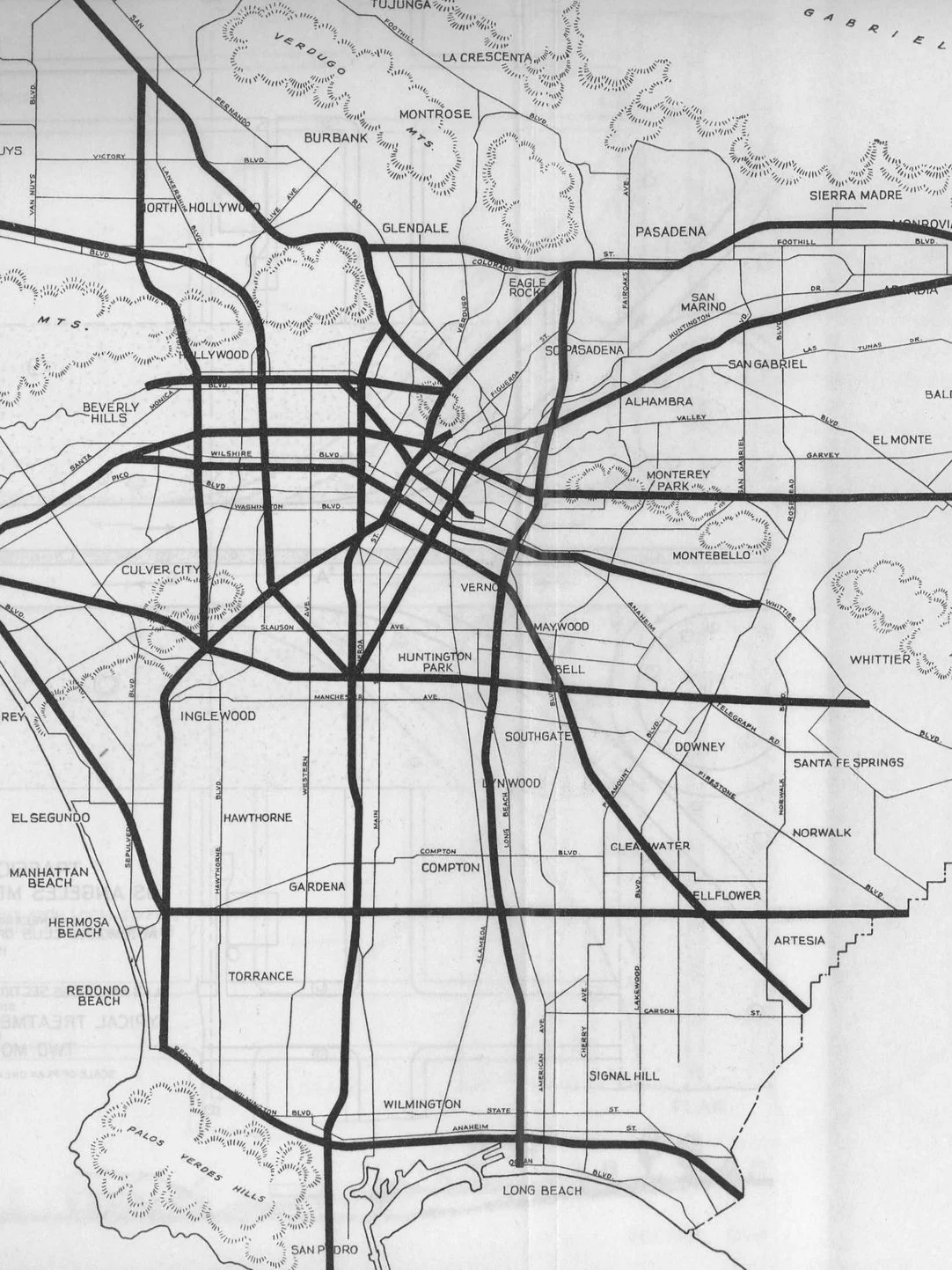

A quick history: In the late 1860s, improvement in the national reputation of Los Angeles became the singular project of several Anglo-American businessmen who had recently settled in the South-land. Embarking on a colorful campaign of self-promotion in newspapers distributed in the larger economic centers of the nation, the group eventually persuaded the Southern Pacific Transportation Company to terminate its transcontinental railroad in their sparsely populated town. The town became a city, which continued to develop along with mass media—popular periodicals, but also world’s fairs, film, and radio—to seduce middle-class settlers to its magic mirror. These same media channels, in turn, become the tools for swaying the growing population to let industry and the automobile gnaw away at the public sphere—the spaces in which public opinions could be formed horizontally and without the influence of moneymen. The successors of those who induced the railroads, of course, later fought to dismantle the region’s rail network in favor of automobile construction throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

Yet despite this unbridled stratification (or, perhaps, because of it), Los Angeles sprang forth diverse communities and subcultures that resisted the social atomization devised by its urban planners, as well as the one-way communication channels envisioned by its media empires. Pushed around by land dispossession, mass transit removal, and aggressive policing, members of the city’s Black and brown communities reappropriated the same mass media technologies peddled by oligarchs to broadcast popular struggle (Malcolm X, already a regular radio presence, gave his famous account of police brutality in Watts in a 1962 broadcast; sound and footage from the 1972 Wattstax benefit concert at the Coliseum— organized to help fund the rebuilding of the neighborhood in the wake of the Watts Rebellion—were subsequently compiled into a double LP and documentary film), while artists, surfers, and other nonconformists found cheap open space and camaraderie in those pockets of town the mortgage lenders had overlooked.

The English critic Reyner Banham took up a teaching position at UCLA the same year as the riots in Watts. Fascinated by his new home—so different from his native Norwich, and so unliked by uppity colleagues—he began recording his impressions on paper. Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971) is a collection of punchy essays and colorful images in which Banham tried to get his arms around the megacity. He adapted the most provocative elements of the book in a 1972 television documentary, Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, for a wide British viewership. (At the time, the BBC was eager for edutainment and produced the film.) “I knew Los Angeles long before I got there,” he narrates from the provincial vantage point of Norwich. “From Buster Keaton to Perry Mason and beyond, we’re all familiar with the place already.”

“The old architecture criticism—to the extent that it continues to exist— is wrong to be so slow in accepting the younger generation’s use of new media.”

Mining the gap between screen and topography, Banham couples a novel medium with equally novel writing styles and subjects designed to cater to the demanding late-midcentury media consumer. He glides across Los Angeles as one once flipped through television channels. He’s led along by a fictive visitor guidance system named Baede-Kar, which steers him toward sites that together paint a telling yet incomplete portrait of LA, including the Watts Towers, Muscle Beach, Mattel (“the world’s biggest toy and game factory”), the Gamble House, abandoned streetcar tracks, and the Tail O’ the Pup hot dog stand. And in an effort to do the opposite of whatever a traditional architectural critic would do at the time, Banham solicits opinions from locals who wouldn’t know a Schindler from a schnitzel. A bodybuilder, a private security guard, and Brad “the mobile musician” all give their thoughts on the city, unabridged and often rambling. Halfway through the documentary, Banham hops a tour bus to see celebrity homes and bone up on local lore and other trivia the way the most clueless of tourists do.

Writing in Artforum about Architecture of Four Ecologies, Peter Plagens, an artist then based in LA, derided Banham’s “fly-by-night sociology” as superficial as the mass media that lured the author there from England. For Plagens, Banham’s adoration of automobile infrastructure and atomizing sprawl was a dangerous influence on impressionable minds—even if those impressionable minds were halfway around the world. “In a more humane society where Banham’s doctrines would be measured against the subdividers’ rape of the land and the lead particles in little kids’ lungs, the author might be stood up against a wall and shot.”

The Banham/Plagens standoff established something of a tradition in urban criticism about LA: For half a century, it has often been the interlopers who are mesmerized by the megalopolis, while the locals hone their antipathy into a science. Think Charles Jencks, inveterate compiler of curios, on the one side; on the other, Mike Davis raining fire and brimstone on those for whom credulity is an ever-present state of mind.

To the credit of the Davis-heads, Los Angeles has become heavier from the growth of the FIRE sectors that have together ratcheted up class strife in the city. At the same time, Los Angeles has become infinitely more lightweight from the outside. Though Instagram and X, formerly Twitter, maintain headquarters hundreds of miles north, Los Angeles County has been utterly transformed by social media’s insatiable thirst for content.

For four months beginning in January 2023, LA gained an unofficial “critic-in-residence” in Oliver Wainwright, a globe-trotting architectural authority from England who documents his travels on Instagram and X and, to a slightly less frequent extent, in zippy articles for the Guardian, one of the few British daily newspapers without a paywall.

With the instincts of a shitposter, Wainwright quickly saturated his social media profiles with the kind of memeable weirdness LA offers up to its most observant spectators: a mural dedicated to a departed celebrity mountain lion (rest in power, P-22), a self-eroding Los Angeles River, and the boundary-blurring interiors of the only student housing project ever designed by John Lautner. In Los Olivos, a wine tasting town orbiting Los Angeles, Wainwright discovered “the ultimate American facade— pressed metal ‘stone effect’ trailer skirting panels, nailed on to a wooden false front in an old western town [drooling face emoji].”

Continuing in the English habit, Wainwright spent his extended stay in LA untangling the celluloid from the concrete. Though careful not to paint the bad as good (a strategy favored by Jencks, who, though hailing from Baltimore, refashioned himself into a minor English aristocrat), his critical notices about Los Angeles’s newest oddities tread little ground between ecstasy and woe. A TikTok-friendly video of the (bright) highlights of Super Nintendo World, the most recent addition to Universal Studios Hollywood, was served up as a teaser for the Guardian review—itself a breathless summary of a sugar-fueled field trip interspersed with only a brief admonishment of Universal’s price-gouging techniques that make the amusement park increasingly inaccessible to the average Angeleno. A similar delirium colors Wainwright’s reflections of an Instagrammable “pot crawl” that marvels at the flashy interiors of the city’s cannabis boutiques without mention of the local prisons currently holding tens of thousands of Californians for prior cannabis convictions.

Pulling on a far less endearing thread of Southern Californian excess, Wainwright rightfully decried the debut of the Vengeance, a $285,000 military-grade street legal tank designed and manufactured by Irvine-based company Rezvani Motors that now lumbers across Sunset Boulevard in growing numbers. “While its competitors offer heated seats and optional roof-racks, this souped-up SUV boasts bulletproof glass, blinding strobe lights, electrified door handles, and wing mirrors that can shoot pepper spray—handy for putting those pesky cyclists in their place,” he notes.

Toward the end of his brief tenure in the spring, Wainwright squeezed in a scathing review of a multimillion-dollar building—one that might have charmed Banham for its unabashed exuberance in the parochial tradition. His reflections are best summarized by the caption of an Instagram post: “The (W)rapper tower by Eric Owen Moss—designed in 1998 and finally built—stands as a gas-guzzling tombstone to a time when architects occupied an autonomous fantasy realm while the planet burned. Review now online #linkinbio.” Though Wainwright did not win any favors among the homegrown, and now aged, architectural elite—including Moss and Morphosis’s Thom Mayne, whose recently completed Orange County Museum of Art he also trashed for its hastily finished details and impotent hubris—his condemnation was liked and shared by a large virtual fan base of international architects.

While it was never Wainwright’s intention to offer a comprehensive take on Los Angeles, his few but high-impact memetic columns on the region’s freshest horrors and escapisms might give the impression that, like the social media on which it is diffused, the city is primarily composed of baffling highs and lows that can be collectively navigated as an assortment of competing images. We can take in these images, even immerse ourselves in them, but can do nothing to change the conditions they alternately depict and conceal.

The old architecture criticism—to the extent that it continues to exist—is wrong to be so slow in accepting the younger generation’s use of new media. But new media has yet to be sufficiently applied to the insurmountably difficult task of describing LA with both the levity of a Banham and the sobriety of a Plagens.

The glamorous images of Los Angeles that bounce around the world on countless real estate reality shows and social media posts eclipse the everyday realities of homeless encampment sweeps, police raids, and air pollution that have only intensified here in the last fifty years. Los Angeles continues to dare outsider critics to “solve” its urbanistic puzzle, and it likely always will. But only those who can offer impressions heavy enough for downbeat locals, yet light enough to ride the wave of the city’s global image explosion, will be able to cut through the chatter.